BY AMER MAHMOOD AND G. CONNOR SALTER

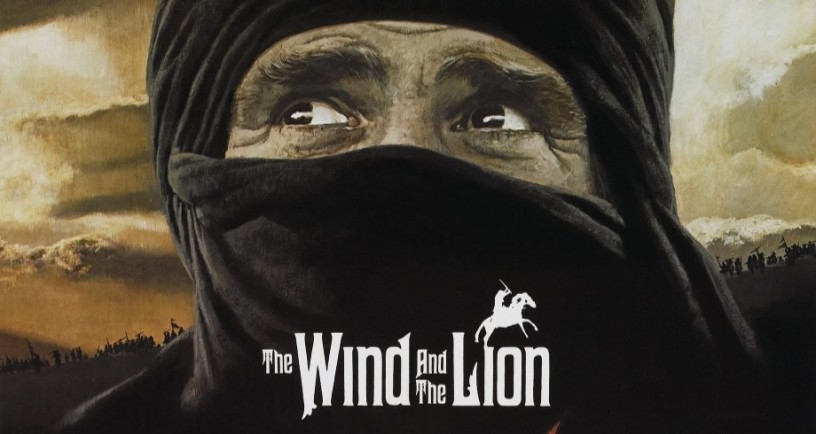

What happens when a Muslim and a Christian watch a movie about Christian-Muslim conflicts in the Middle East? Not a contemporary movie, one of those stirring Hollywood desert epics that people worry hasn’t aged well? Something like The Wind and the Lion, the 1975 movie directed by iconic but much-debated filmmaker John Milius?

One of us (Connor) was writing an article on Milius and felt The Wind and the Lion is a fun movie that few people discuss today. He couldn’t figure out if the niche status meant it had aged poorly or if it was offbeat compared to more famous desert epics. So, he reached out to Amer with an offer to watch the movie and compare notes. What would a Muslim viewer see in this movie?

The result was a fun discussion about how 1960s-1970s adventure movies portrayed Islam and pre-World War I history. The following is based on our discussion. Since our ideas developed as we spoke to each other after seeing the movie, it became impossible to attribute every single contribution we individually made. Instead, we tried a melded approach: especially strong insights from one or the other have been noted. The rest is a melding of our perspectives.

So. What is The Wind and the Lion?

Like most desert epics, it is (sort of) based on a true story.

The Real Story of Raisuli and Perdicaris

In the early twentieth century, Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni (or Raisuli, in early accounts like Walter Harris’ 1921 book The Morocco that Was) ruled the Jebala tribes in Morocco. Sometimes called “the last of the Barbary pirates,” he frequently kidnapped Westerners for ransom and raided other tribes for their resources. He was tolerated for his military power and status as a sharif—a descendant of the prophet Muhammed. In 1904, he kidnapped Ion Perdicaris, a Greek-American man living in Morocco with his adult stepson, Cromwell Varley. Like earlier occasions when he kidnapped British citizens, Raisuli demanded a ransom. However, Perdicaris’ American citizenship and the fact that 1904 was a presidential election year made a difference. Teddy Roosevelt was campaigning and needed a cause. His cause became “America wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead.”

The ploy worked—even though, as Harold E. Davis and Thomas H. Etzold point out, Perdicaris’ American citizenship was in question. Raisuli received most of his demands, but Perdicaris and Varley were released unharmed in June 1904. Roosevelt easily won the election. Perdicaris returned to his home in England and later wrote, “I go so far as to that that I do not regret having been his prisoner for some time. I think that, had I been in his place, I should have acted in the same way. He is not a bandit, more a murderer, but a patriot forced into acts of brigandage to save his native soul and his people from the yoke of tyranny.”

O. Henry spoofed this hostage crisis in his 1905 short story “Hostages to Momus.” Today, the Perdicaris Affair appears in debates about Stockholm Syndrome or early Islamic-American conflicts, as in Akbar Ahmed’s book The Thistle and the Drone. In 1975, four years before the Iranian Revolution and decades before the War on Terror, it was prime material for a good old-fashioned desert adventure movie. No one made adventure movies like John Milius—screenwriter of projects like Jeremiah Johnson and Apocalypse Now and director of Conan the Barbarian and Red Dawn.

The Movie’s Genesis

Milius learned about the Perdicaris Affair through the August 1959 issue of American Heritage magazine. In Big Bad John: The John Milius Interviews, he tells Nate Segaloff that he later read the full story in Rosita Forbes’ 1924 book El Raisuni: The Sultan of the Mountains. Milius concluded he could make it into a movie, but “instead of a man being kidnapped, it should be a woman, and the relationship between the two of them should be quite sensual without them ever doing anything.” He later said on The Wind and the Lion director’s commentary that he was thinking of Victorian boys’ own adventure stories like Rudyard Kipling’s works: stories where women are always getting captured by exotic foreigners and the plot becomes a “will they, won’t they?” romance where the flirtation never develops into something more.

So, Milius changed the hostages to a widowed woman with children—originally a grandmother with her grandchildren. Studio executives suggested the movie would play better as a movie about a young woman being kidnapped. Ultimately, Candice Bergen played Mrs. Eden Perdicaris, a young American widow with a son, William, and a daughter, Jennifer. Sean Connery played Raisuli with brownface makeup, which was not unusual for the period, although Milius joked in the director’s commentary that Raisuli obviously learned English from a Scottish soldier.

The movie’s title comes from a message that the movie (and tie-in novel written by Milius) claim Raisuli sent to Roosevelt after the situation was resolved:

“To Theodore Roosevelt—You are like the wind and I like the lion. You form the tempest. The sand stings my eyes and the ground is parched. I roar in defiance but you do not hear. But between us there is a difference. I, like the lion, must remain in my place. While you, like the wind, will never know yours.”

Connor could not find any record of Raisuli sending this message and suspects it’s an invention. On the director’s commentary, Milius admits that he made up a speech in The Wind and the Lion in which Teddy Roosevelt compares America to a grizzly bear… and gave a copy to a national park that thought it was genuine and wanted it for a plaque.

So far, it’s clear that Milius was more concerned with telling a fun story than an accurate historical drama. The fact the first scene says the kidnapping happened on October 15, 1904, six months after the actual kidnapping, confirms that Milius is playing fast and loose with the facts—which has interesting repercussions for how he portrays the setting and characters.

The Movie Begins

The movie opens in Tangier, Morocco. Amer noted that at the time, Morocco was the last Islamic monarchy west of Istanbul/Constantinople. As the Bashaw of Tangier observes in the movie, Morocco is in a curious place in 1904: the French, the British, the Spanish, and the Germans all have vested interests in the region. Amer observed that we get a sense of this in an opening scene when Raisuli’s armies pass through a camp of Muslim guards flying a French flag.

Not only is this a story about international tension: it’s a story about cultures clashing. For example, after Raisuli kidnaps the Perdicaris family, American diplomat Richard Dreighton visits the Sultan of Morocco for help. He brings an expensive gift, several lions in a cage, to the Sultan’s palace in Fez. When he arrives, Dreighton asks a servant why there are no roads to Fez—“I had to bring these lions by camel.”

“The ease of others is not the concern of the Sultan,” the servant answers.

Dreighton replies confidently, “We’ll build the road someday.”

The servant scoffs. “A road here? Foolish. The desert is like the sea. You cannot build a road in the sea.”

Dreighton says, “We will. We have men that can do anything. Absolutely anything. We have men that can fly.” Amer noted that Westerners did eventually build a road to Fez. Connor noted the movie also references Roosevelt’s work on the Panama Canal. American imperialism at its peak permeates the movie.

While the American leaders are portrayed as powerful and haughty, the American hostages are portrayed as appalled by Raisuli’s Muslim pirates. When Raisuli executes two men who stole well water and dates from his land, Eden Perdicaris acts shocked. Amer noted this is perhaps an anachronism: the British and Americans were well acquainted with capital punishment in those days.

But there’s nuance to this depiction. The Americans see the Muslims as backward, but the Muslims see the Westerns as uncouth and wasteful. Before executing the well thieves, Raisuli points at the well as he tells Eden why his people revere him for making war on the Westerners:

“You see the man at the well, how he draws the water. When one bucket empties, the other fills. It is so with the world. At present, you are full of power, but you are spilling it wastefully, and Islam is lapping up the drops as they spill from your bucket.”

Eden responds to Raisuli’s disdain for the West with confidence that he will not get what he wants. When Raisuli explains that the British have always met his demands, she replies, “Well, you’ll not have your way with the Americans!”

When Eden asks why he kidnaps women and children, Raisuli replies that he will take women and children because as much as he would like to fight the West openly, “they do not fight as men. They fight as dogs.” Instead of honorable warfare like swords or rifles at worst, the Europeans use “guns that fire many times promiscuously and rend the earth. There is no honor in this. Nothing is decided from this. Therefore, I shall take women and children when it pleases me.” Although not particularly Islamic, Amer noted it might been an effective war tactic for some Muslim militia groups: unusual methods deployed to counter the enemy’s stronger firepower.

While this is a culture clash narrative, the movie doesn’t try to make Islam look graceless or primitive.

Cultural Details

For all the changes to the historical record, there are moments when the research is spot-on. For example, at one point, Raisuli talks about tying the camel—a quote from one of the hadiths. Amer noted how the sets, particularly the riyad layout of houses seen early in the films, are depicted beautifully. However, it would be wrong to infer the lavishness of these places were restricted to the elite or rich.

Yet overall, the movie does seem more interested in creating a charming, over-exotic Arabian effect than getting every detail right. The first scene of Dreighton and his boss, Consul-General Samuel R. Gummeré, meeting the Bashaw of Tangier involves the Bashaw pompously eating a date while he drops lines like “It is, as it shall be” and “Better to serve the leopard than the fox.”

Other times, the movie gets minor details about Islamic practice wrong. When Raisuli’s men are depicted praying to Mecca, they kiss the ground instead of prostrating. In another scene, when Raisuli’s people see his returning army, they start prostrating, and their actions morph into a congregational prayer. Amer noted their motions are all performed, well, like non-Muslims pretending to pray like Muslims.

Still, at other times, the research is blatantly, unabashedly erroneous. Rasuili appears foreign and brutal when he executes the two men who stole his well water and dates, but their theft does not equate to capital punishment under Shari’ah law.

When Eden asks how devout his faith is, Raisuli replies that he prays to Mecca five times daily. Notably, while he mentions taking the right time to pray, the right time is never established. When Eden asks how he has time for this with all his kidnapping and killing, he says, “If I miss the morning prayer, I pray twice in the afternoon. Allah is very understanding.” In reality, missing a prayer time is a serious violation.

Yet even when the research is dubious, the dubiousness is standard for the period. Amer noted that Moustapha Akkad’s movie The Message was a significant breakthrough in getting the research right—which came out a year after The Wind and the Lion. So, this is before the watershed moment that changed everything.

It’s also worth noting that we expect more accuracy from dramas than from humorous movies.

The Humor

While The Wind and the Lion isn’t strictly a comedy, it does feature a lot more humor than Lawrence of Arabia.

In Raisuli’s first scene, he grandly steps onto his horse from his men’s backs. The horse bucks, and he gets scraped in a tree. Eden laughs at him, but Raisuli slaps her for laughing. “I am the Raisuli,” he says. “You will not laugh at me again.”

Alfio Leotta suggests in The Cinema of John Milius that this scene parodies desert epics—subverting the regal behavior, creating humor, and restoring the tone with drama (Raisuli slapping Eden). Amer wondered if it was planned or something that happened accidentally on the set (working with animals is unpredictable) and the actors played along, deciding to keep the footage. It’s quite possible. Planned or not, it creates a tone where the movie is poking fun at audience expectations.

Humorous, often cartoonish, behavior doesn’t just happen at the movie’s start.

The first morning after capturing her, Raisuli’s men wake Eden up by prodding her on the bottom with a gun. They hand her some undergarments from her luggage and cackle at her as she hides under a blanket so she can change.

Later, there is a cartoonish attitude to violence when Dreighton gets his meeting with the Sultan. The Sultan is playing polo on bicycles. After a comical cycle crash, he laughs hysterically, and a weapons trader with an eyepatch (Milius in a cameo) offers him a chance to fire a Maxim gun. As Amer put it, “What a careless thing to do!” The Sultan fires into some trees, then sulks and declares the gun is broken when it stops firing.

There are also humorous inconsistencies. Amer notes that Rasuili’s comment about Allah “being understanding” if he misses prayer times is funny because Rasuili makes excuses for himself but not for others (like the thieves he executed).

However, if Milius uses the Muslim characters for humor, he does the same with the Americans. Roosevelt has a party at the movie’s midway point, and Secretary of State John Milton Hay commits a faux pas. He talks in condescending, broken English to a Japanese general. The general stands up, gives a toast to Roosevelt in fluent English, then looks at Hays and says, “Do you likee speechee?” Hays reluctantly nods. So, Milius seems to be poking fun at the American officials’ arrogance as much as he makes fun of the Arabians.

Connor noted there are also moments when Milius specifically treats the Americans like cartoonish warmongers. Dreighton and Gummeré meet with other Americans in Tangier to discuss the situation as tensions escalate. Captain Jerome gleefully suggests what they can do: “military intervention!” Instead of speaking softly and carrying the big stick, they will use the big stick. They will capture the Bashaw of Tangier, pressuring the Sultan to arrest the Raisuli and retrieve the Perdicaris family. Most likely, the other Western forces in Morocco will get behind the American forces to avoid a larger conflict. Gummeré notes that if they fail, they will all be killed and the Western forces in Morocco will fight each other. They could start “a world at war… a world war… that would be something to go out on.” Like the soldiers in Apocalypse Now, these men seem excited at the chance of a great war.

The humor accomplishes a few things. Connor noted that it does not make the movie quite a satire like Doctor Strangelove, but it does make the movie more impishly funny than viewers would expect. Milius made this movie after the famous 1960s desert epics like Khartoum or Lawrence of Arabia, movies that took themselves very seriously. Milius seems to balance gentle spoofing with homage, like what his friend Steven Spielberg accomplishes in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Amer noticed something even more important: the humor makes everyone endearing. Everyone looks a bit foolish, so there is no noble Westerners vs. idiot Easterners dichotomy. “Through humor, you can make the foreign, the exotic, the strange, a little more comfortable to be with,” Amer pointed out.

That need to make people endearing was perhaps especially important at the time. This was before The Message set new standards for getting Islam right, but it was the oil crisis period—a time when irritating Arabs was a very bad idea.

There are even some nuances to the comedy. For one thing, there’s a childlike sense of adventure—especially with the Perdicaris children, William and Jennifer.

A Child’s View of Adventure

While William and Jennifer are initially frightened at being kidnapped, they also become fascinated by their new experiences.

After Raisuli makes his initial ransom demands, his men bring back bad news—including a messenger’s tongue on a plate. Raisuli’s men put the plate on the ground, and the children lean down to look at the tongue and prod at it. The scene is quirky and funny because the tongue fascinates the children. Like scouts inspecting a dead squirrel they found in the woods, this is cool, a diversion.

Leotta makes an interesting suggestion about the children’s role in this movie. He suggests that Milius references not only Lawrence of Arabia but also A High Wind in Jamaica, a 1960s adventure movie in which children accidentally end up on a pirate ship. While flawed, one of the movie’s strengths is how it generates humor from the children treating their time on the pirate ship like a pleasure cruise. In contrast, the pirates fear the children (because children on a ship are bad luck and injured children could mean a murder trial). Like the accidentally kidnapped children in A High Wind in Jamaica, Jennifer and William treat being kidnapped—even the gruesome moments—as something new and exciting.

This theme becomes especially clear in a scene where they contemplate their fate. William shows a knife that one of Raisuli’s men, Gayaan the Terrible, gave him. Jennifer asks what their captors will do, and William talks about joining them and becoming fellow brigands. “Even girls?” Jennifer asks. “Yes,” William replies. “But you’ll have to wear a veil.”

Amer highlighted that the children’s indifference shows the period: this is a time where being captured by another people group, or more generally moving between one or more rulers, had different overtones. People often got in and out of trouble, subjects of one or another group, depending on which empire’s borders were shifting. There were definitely dark moments (people falling under authoritarian leaders, for example). But the shock level was different in a pre-War on Terror world—especially a pre-World War I world in which imperial power was normal and someone would presumably intervene if Westerners got into real trouble. It wasn’t assumed that being captured in the Middle East meant being killed and thrown in a hole, as many people would fear today.

Connor noted that not only does the nonchalance show how being kidnapped abroad has different overtones today. It’s also important to note that William and Jennifer believe they will be treated as equals if they stay with Raisuli. Jennifer assumes she’ll fight alongside the brigands—not, as is more likely, becoming a servant, enslaved, or married off to someone. That may show that the children assume that being American means no one will hurt them, but it also relates to what Milius said about writing a Kiplingesque adventure. In Victorian boys’ own adventure tales, being captured becomes an opportunity for adventure, and equality with captors is assumed. This is just as much a movie referencing Kipling as it references David Lean.

Along with the multilayered humor, there are some curious examples of guile throughout the movie.

Guise and Posturing

While Milius often gets dismissed as making cartoonish movies celebrating cartoonish warriors, there is often a sense that the heroes are tricking people. Connor noted that before making The Wind and the Lion, Milius wrote or directed several movies (Evel Knievel and Dillinger) about larger-than-life men who are clearly cultivating public personas. Perception is key to both the protagonists and antagonists in The Wind and the Lion; characters are forever pretending to be one thing or another.

Roosevelt’s first scene shows him posing for photographs, standing next to a globe, his hand resting next to Morocco. Later, at Yellowstone Park, he lets journalists sit nearby and take his quotes as he describes killing a grizzly bear. After a particularly good comment, he turns and repeats the quote to make sure one journalist gets it right.

Sometimes, characters admit they are acting in a role. When Raisuli and his hostages reach his garrison, William asks if he worries about invaders with machine guns. Raisuli mocks those who need machine guns, giving the impression he’ll never need them. When no one laughs with him, he says, “Well, maybe I don’t believe it either.”

Inside the garrison, Eden asks Raisuli what he will do next. He clarifies that he never planned to kill her or her children. As Amer notes, this is the genuine Islamic value in the situation—needless killing is needless killing. Eden responds to the discovery that Raisuli has been playing at being a deadly killer by weeping and admitting she has been playing a pose, too. She doesn’t explain what she has been pretending to be, although the implication is she’s been pretending to be tough and contemptuous.

Meanwhile, the Americans discover they were mistaken when they thought Raisuli was an outlaw that the Moroccan authorities could easily remove: the Sultan tells Dreighton that Raisuli is his uncle, so he cannot oppose him.

When Captain Jerome and his men stage their military intervention in Tangier, their attack has a curious mix of expectation and subversion. They enter the Bashaw’s palace like invaders but encounter no resistance until they reach the gates. Even when they have broken in, the Bashaw is unperturbed by being captured. He knows their show of force will never lead to his bodily harm. As established earlier, many nations have interests in Morocco—too many for America to risk assassinating him.

As the story reaches its final climax, a deadlier charade develops. Western forces report hat they will give Raisuli what he wants, collect the hostages, and then let Raisuli go free. When it becomes clear that Raisuli is being cheated, both his men and his hostages find this charade a step too far. Treachery is impermissible.

But if Raisuli is the villain in The Wind and the Lion, why is his being double-crossed a terrible thing? The answer is that the movie has afforded him reverence all along.

Raisuli as Saintly Rogue

While The Wind and the Lion is an adventure story, and all adventure movies need a memorable villain, Milius doesn’t set up Raisuli as a standard villain. He is a saintly figure.

Amer noted this is somewhat obvious from the casting. Yes, casting a Western actor and using brownface makeup appears insulting today, but it was standard then. The more important question is who plays the Islamic villain. Having Sean Connery, then at his career’s peak as a leading man, play the Raisuli means he must be an admirable figure. People didn’t hire Connery to play irredeemable villains.

From the beginning, he’s shown as an important, respected man. He uses the back of people to climb up a horse, showing their devotion to him. After being captured, William tells his mother, “He has the way about him, doesn’t he?” As Raisuli says in his telegram to Roosevelt, he is the lion—which Amer pointed out is associated with nobility.

Raisuli says Allah sees all—and since he is a descendant of Muhammad, it’s clear that he is saying he sees all. At one point, he tells Eden that he does not need guards to see where his “guests” are. He sees himself as having divine favor.

His regal, saintly, enchanting presence becomes clearest in a nighttime scene where Raisuli tells his life story to the Perdicaris family. While his hostages and his men hunch around a campfire, he describes how his brother turned against him, imprisoned him, and how he escaped to become an outlaw. He says he survived each tricky situation because the barakah was with him. Barakah is a blessing, an extra portion of favor from Allah. He believes he enacts the Will of Allah. His guests seem awed by his claims.

Connor noted that the scene also connects with the childlike wonder element: William, Jennifer, Eden, and Raisuli’s men look like children hunkered around a campfire. One bandit even looks at Willaim while eating meat as if deciding whether to share his snack. Meanwhile, Raisuli holds court and tells his story. He is a violent but saintly, a kidnapper and a benevolent scoutmaster.

If this is true, how does he relate to Eden? What makes this movie, as Milius puts it, a Kiplingesque romance?

Kiplingesque Romance

When she is captured, Eden puts on a tough face with Raisuli, only for him to flirt and parry. On her first morning as a hostage, she informs him that God will listen and avenge her if he harms her or her children. Raisuli listens and asks, “Do you play checkers?”

“I play chess.”

“Better.”

Later, they play chess—Eden winning when she checks his queen—and argue about what will happen if Raisuli doesn’t give her up to the American government. Eden continues to speak tartly, but enjoys trading barbs with him.

The second night after she’s captured, Raisuli has Eden sleep in his tent. He closes the tent flap by slashing it with a sword. He playfully pokes at her coiffed hair with his sword, then puts it between them as he lies down. She keeps a pillow before her face like a frightened child but appears to fall asleep.

The scene is an ambiguous interplay between perceived danger and apparent attraction. Connor noted that Raisuli poking at her hair is like playing with a pet, indicating that he has the power, yet without actually harming her. Putting the sword between them, where Eden can easily get it if Raisuli tries anything, resembles scenes in adventure novels like Tarzan of the Apes, where the man gives the woman a weapon.

Amer noted that it’s curious that Eden doesn’t seem overly concerned about where her children are. Admittedly, we assume she has some idea—a servant appeared early in the scene to tell her that she’ll sleep in the tent, so we can assume the servant informed her where William and Jennifer are. But the fact she doesn’t ask suggests she’s focused on Raisuli… either too frightened or too fascinated by him to remember she’s supposed to be a protective mother.

Later, Eden attempts to escape with her children, but the outcome isn’t what she expects. They bribe a man to take them from Raisuli’s garrison, and the guide takes them into a sinister-looking camp. Men come toward them, jeering and jesting like salivating hyenas approaching prey. Then Raisuli appears in the distance. Eden, seemingly helpless a moment ago, grabs a spear and seems able to handle herself. Raisuli appears and overpowers the crowd like a one-person army. Eden almost climbs into his hands as if entranced and rides back with him, her children following. “Mrs. Perdicaris,” Raisuli says, “you’re a great deal of trouble.”

Eventually, they tell each other their first names. His name is Ahmed, but she calls him Mulai—a title meaning lord.

When the combined Western forces present Raisuli with an offer, Eden picks up on the fact that something devious is happening: some attempt to make Raisuli look weak. She tells him to reject the deal. In one of the movie’s best lines of dialogue, Raisuli turns on her: “Why do you do this? I do not take council of my men, let alone women—you are not even one of my wives!”

Eden looks surprised and says, “I should say not!” It’s hard to escape the sense she is horrified for a different reason. She’s frightened because Raisuli has said out loud something that neither of them have been willing to admit: that they’re attracted to each other. As she said earlier, she has been pretending to be his enemy.

Connor noted that the wives’ line is interesting since we only see Raisuli’s wives in one scene. When Raisuli and his men arrive at his garrison, the camera shows several women covered in veils, their faces not visible, standing on a terrace. The camera puts them in the background. Eden is on another terrace in the foreground. She talks to Raisuli about his plans and learns she won’t die. So, we have this important bonding moment when she perhaps admits she has feelings for him, with his silent wives in the background.

Ultimately, Raisuli takes the Westerners’ deal, which he knows is likely a trick to capture him. He compromises rather than fighting back. He is not following her advice then, but he is perhaps becoming more like her—more cooperative.

If he is becoming more cooperative, at least for her sake, then she becomes more warlike when she sees the Western forces will cheat Raisuli. As she expects, he gets captured—the Americans turn him over to European troops. With a rifle in hand, she convinces Captain Jerome to help her rescue Raisuli. Her reason? President Roosevelt wanted the Raisuli free if he followed his end of the bargain. So, she has become warlike—more like Raisuli—and shown her new respect for her enemies.

After the inevitable battle scene, Raisuli escapes into the desert. Before he leaves, he looks at Eden and says, “I’ll see you again, Mrs. Perdicaris. When we’re both like golden clouds on the wind.” Without being an explicit reference to Jannah, paradise (which is often described as a garden), the cloud imagery does suggest he is talking about the afterlife. This may be the clearest example of Raisuli challenging accepted norms. Does he imply that she will be his wife in the afterlife? It’s hard to square this with Islamic theology since they didn’t marry. Admittedly, she talks about believing in God earlier in the movie, so perhaps we can argue that she comes from “people of the book” (Muslims, Christians, or Jews), and that makes it permissible for him to claim her as a wife. However, an orthodox Muslim wouldn’t likely approve of Raisuli’s comment. We are back to the idea of him being a saintly rogue.

Sympathetic Terrorists?

Of course, the attraction doesn’t change Raisuli being a pirate. Some scholars have critiqued how sympathetic he appears in the story. In a March 2015 article for New English Review, Norman Berdichevsky makes an interesting claim that the movie offers a “romantic glorification of violent Islam” while also using the setting for Vietnam commentary. In his view, Raisuli is a sympathetic terrorist, and Roosevelt fills a similar position to Lyndon B. Johnson during the Vietnam War. The story becomes about an American desire to make Islam look good and maybe use that label as a way to talk subversively about America’s anger that Vietnam had ended so badly despite so much optimism that America could handle that overseas crisis.

There probably is a Vietnam undertone to The Wind and the Lion. We can extend that to some of Milius’ friends. George Lucas, his film school classmate, freely admitted he was thinking of the Viet Cong when he designed the rebels in Star Wars. It is also fair to say that Raisuli would be considered a terrorist today. There is a reason that Ahmed includes the real-life Perdicaris Affair in The Thistle and the Drone, a history of Islamic-Western violence. The struggle with Berdichevsky’s fascinating thesis is that Milius sets up Roosevelt and Raisuli as images of each other. Whatever we think about Raisuli’s position also applies to Roosevelt.

Roosevelt and Raisuli as Mirror Images

From the start, Roosevelt is as much a lovable rascal as Raisuli. His first response to Raisuli’s kidnapping is to send an Atlantic fleet to Morocco. Hays points out that it would be illegal, and Roosevelt says, “Why spoil the beauty of a thing with legality?”

While Milius doesn’t discuss Roosevelt’s religious views, they make him a complementary figure to Raisuli. Connor recalled that Benjamin J. Wetzel’s book Theodore Roosevelt: Preaching from the Bully Pulpit, describes Roosevelt as a complex religious figure. Raised a devout Presbyterian, his faith became more skeptical after Valentine’s Day, 1884: the day his first wife and his mother passed away in the same house. While it wouldn’t be accurate to say that Roosevelt lost his faith, Wetzel sees the post-1884 Roosevelt as a man who deeply believed that Christianity should inform behavior while struggling with how much he still believed in some Christian precepts. In other words, like Raisuli, Roosevelt was religious but not devout enough to be a reputable saint. Had they met in person, they might have been friends.

The idea that Raisuli might like Roosevelt if they met comes up when Eden declares the Americans will not play his games like the British have. She warns that Roosevelt is a brave man, and Raisuli asks if Roosevelt will come himself. Then he asks what kind of rifle Roosevelt carries. Finally, he sees a chance to fight someone who will use swords or rifles, not machine guns and bureaucratic policies.

Sometimes their dialogue even mirrors each other. Hay tells Roosevelt about Raisuli’s last hostage situation: how the hostage came back alive and friendly with Raisuli, but Raisuli sent “parts of” the Spanish and French emissaries back. Roosevelt declares, “Parts of them? Obviously, he has no respect for human life!”

When Raisuli’s men bring bad news about negotiations, they bring a part of an emissary—the tongue on a plate. Raisuli isn’t horrified by the tongue, but when he hears the bad news, that the Americans will kill him if he doesn’t return the hostages, he turns to Eden. “Does this president, this Roosevelt, does he have no respect for human life?”

This image of Roosevelt as a maverick in his own right crystallizes in the movie’s Yellowstone Park scene. As mentioned earlier, Roosevelt tells journalists about a grizzly bear he has killed after it attacked some horses. The scene isn’t about the famous “Teddy’s Bear” from Roosevelt’s 1902 hunting trip. Still, even if Milius isn’t telling us the story of “Teddy’s bear,” he is developing that iconic image that made Teddy famous. Yet it’s not a cute and cuddly grizzly bear. Roosevelt says the grizzly bear summarizes America because the grizzly bear’s fierceness drives others away. The yearning to push boundaries makes the grizzly bear and America more feared and respected than loved.

That label could equally apply to him: at the birthday party, Hay jokes that Roosevelt is becoming a good brigand. Later, the two men temporarily fall out when Roosevelt behaves too much like a brigand: Hays argues with Roosevelt over approving Jerome’s military intervention. While Hays is the pragmatist seeking a bloodless solution, Roosevelt doesn’t mind it becoming violent. Roosevelt and Raisuli both relish the idea that this could become a battle.

After he argues with Hays, Roosevelt talks to his children about Raisuli. He says sadly that “the world is fast outgrowing pirates, of that sort anyway,” comparing Raisuli to more respectable pirates like J.P. Morgan. Alice—daughter of his late wife, the child who seems to understand his complexity best—suggests that he likes Raisuli and Morgan even though they are his enemies. Roosevelt agrees with her: “Sometimes one finds that your enemies are a lot more admirable than your friends.”

Raisuli shows that he understands how alike he and Roosevelt are in the final scene, in which his “wind and the lion” message is relayed to Roosevelt. They are both powerful men—the lion equals nobility, Raisuli is noble, and Roosevelt is overpowering like the wind. Both have problems—Roosevelt “will never know his place,” probably because America isn’t going to tolerate maverick presidents after him. The War to End All Wars won’t leave any more room for men who glory in war. Raisuli, the lion who will remain in his place, knows he will not end well. There won’t be any more Barbary Pirates. But he will live his life to the last on his terms.

The Wind and the Lion in Context

The idea of the hero and villain finding they have much in common is not unusual in Milius’s movies. Leotta notes that this theme especially appears in Dillinger, where Milius alters historical facts to make Dillinger and Purvis seem like twins separated at birth.

Connor notes that given this theme, it’s interesting that Leotta compares Milius to David Lean. In this movie, Milius’ approach is more like Basil Dearden, who directed the 1966 desert epic Khartoum. That movie features a British general, Charles George Gordon, realizing the self-proclaimed Mahdi he fights in Sudan is much like him: they are both singled-minded religious men devoted to a cause.

Or, if we want to look at Milius’ movies as a whole, he resembles his contemporary, Michael Mann. Mann’s work (most famously the movie Heat and the TV show Miami Vice) usually features urban crime. Still, like Milius, Mann likes stories about two male warriors who oppose each other only to realize they have much in common. Heat includes a cop and bank thief comparing their lives over coffee in a diner. Conan the Barbarian ends with the villain saying to the hero that he has defined the hero by being his enemy. Milius wrote a Miami Vice episode, “Viking Bikers From Hell,” where the detective heroes decide after killing their foes in a shootout that the only difference is they have legal protection. Mann and Milius even explore this theme through the same character (Mann’s movie about Dillinger, Public Enemies, appeared in 2009).

In the end, Milius avoids blackballing or praising Raisuli. He depicts Raisuli and Roosevelt as having the same drive and the same problem. What’s a pirate to do in a world outgrowing pirates?

Watching The Wind and the Lion Today

Almost fifty years after its release, The Wind and the Lion continues to be a surprising film. It’s more cartoonish than better-known desert epics, but the cartoonish humor seems intentional. Its historical and cultural research isn’t as rigorous as we would like today, but it does show respect for Islam. It eschews a “righteous Americans vs. barbaric Arabs” storyline for an ambiguous story about two lovable rogues who are more alike than it seems.

It’s hard to say whether it’s an overlooked classic. However, it is quietly complex for its time and a lot of fun.