BY G. CONNOR SALTER

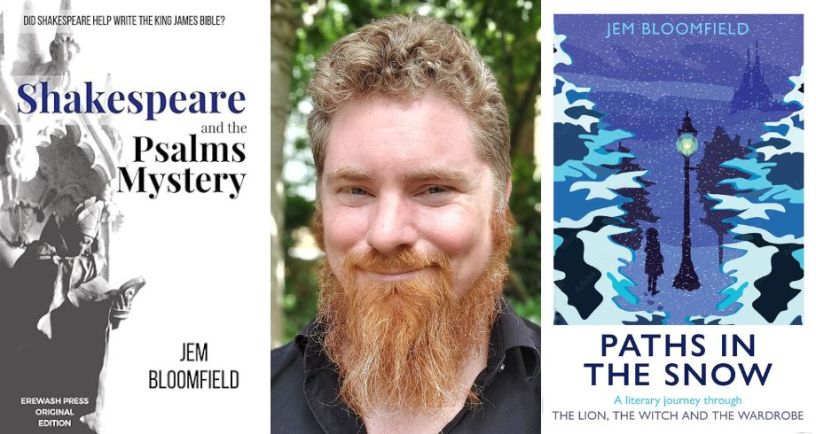

Dr. Jem Bloomfield (PhD, University of Exeter) has described his research interests as “Shakespeare, the Bible, detective fiction, fantasy.” He explores these subjects with his students teaching in the School of English at the University of Nottingham. He has also explored them in his prolific writings. His essays have appeared in various places, including Shakespeare, Theology, Christianity & Literature, California Literary Review, The Strand Magazine, and An Unexpected Journal.

He has published the books Paths in the Snow: A Literary Journey through The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Shakespeare and the Psalms Mystery: Did Shakespeare help write the King James Bible?, Words of Power: Reading Shakespeare and the Bible, Witchcraft and Paganism in Midcentury Women’s Detective Fiction, and Allusion in Detective Fiction: Shakespeare, the Bible and Dorothy L. Sayers.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

What was your first exposure to the Inklings?

I believe I first heard of them as “The Inklings” when I read Humphrey Carpenter’s remarkable book about them. I was a teenager at the time, and was fascinated by the picture he produced of this group of unusual, scholarly, creative people who sat around reading poetry and discussing the great questions.

But my first experience of their work came much earlier, in the late 1980s, when the TV adaptation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was first shown on the BBC. I vividly remember sitting down at tea-time on Sunday afternoons to watch it—and the resultant fear that Maugrim the wolf was lurking in the wardrobe in my own bedroom. (I was, in my defence, quite young at the time.)

Paths of the Snow explored stories that Lewis echoes or alludes to in the Chronicles of Narnia. What were some surprising echoes or allusions you noticed?

One is perhaps the most famous image in the book—not the lion, or the stone table, or the lamp-post, if we judge by the frequency at which people mention it—but the Turkish delight. There’s lots to be said about its moral significance, and its addictive qualities, and how we watch Edmund betray his family for some more of it—but I also became convinced that there’s a connection between it and Dorothy L. Sayers’ detective fiction. Her novel Strong Poison also features a character who gorges himself on Turkish delight, and who has betrayed the trust of his family, and it ends up being the means by which Lord Peter Wimsey gets him to confess to murder…

There are some others which are perhaps more surprising when in combination. I love, for example, the way that Lewis begins The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe which what appears to be an allusion to The Tale of Peter Rabbit (“Once there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy,” but by the time the chapter ends Lucy is in a mysterious wood with echoes of Dante’s Inferno. That sums up for me the dazzling way Lewis weaves together such disparate texts, and the associations which come with them—from those two sets of echoes we have a children’s story, talking animals, an Everyman figure making a journey into a symbolic landscape, and the high stakes of salvation. From that first chapter onwards, he keeps bringing in other intriguing textual traces and allusions.

You talk in your introduction to Paths in the Snow about how there’s a theological richness to the Narnia stories. What are some theological ideas in the series that you wish more people talked about?

There’s plenty of excellent discussion of Lewis and the theology of his fiction—I’ve been very struck by the writings of people like Rowan Williams and Michael Ward, to take just two examples from the bookshelf at my elbow. As to ideas that I think could be expanded on even more, I might like to see Lewis’ concern with doctrine explored more. That can sometimes be a touchy subject for Christian readers of Narnia, since it can feel a bit like “claiming” Lewis for one side of a current discussion, or alternatively as drawing precise lines beyond which we won’t follow him. It can be easier to talk as if he simply made Christianity brighter and more attractive in a general way by writing exciting stories. But Lewis is deeply engaged with the details of doctrine at times.

To take one example, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is an enchanting novel, and it’s also a novel about the atonement. Not only because an innocent character dies in place of a guilty one, and then comes back to life (though that is clearly the hinge of the plot!), but because several theories or models of the atonement are played out through the book. Most obviously Aslan substitutes for Edmund. But Edmund is also the Witch’s prisoner, and he is ransomed back by the lion. The death takes place on what appears to be a stone altar, with a certain amount of ceremony. A war is waged against the armies of the Witch, in which the lion is the victor. A number of the animals are healed by the breath of Aslan. This seems to me a fairly thorough working-through of a series of theories of the atonement—ransom/ satisfaction, sacrifice, penal substitution, Christus victor, healing/ restoration, etc. These theories or models become the framework of the story, not to point out a message to take away, but as the events and experiences which constitute the novel itself.

There are other moments when Narnia is intriguingly engaged with the details of doctrine. The fatal mistake that the White Witch makes is because her magical knowledge stretches back to the very beginning of time—which sounds very impressive until you recite one of the creeds and realize this means she cannot remember anything begotten before all worlds, and thus does not know about the second person of the Trinity. A relatively abstruse point about the doctrine of the pre-existent Logos becomes a major plot twist—and the more one comes to know of Christian doctrine, the more alive and exciting the novels become.

There’s another point which springs to mind, about the way the Witch is described when she first appears on a sledge drawn by reindeer, which I think is a very clever way of demonstrating that Narnia is a non-Manichean universe, but I have rather run on, and that one’s in Paths in the Snow.

You delivered a paper in 2021 where you argued Tolkien scholarship has reached a “post-pop” stage, where now that Tolkien is accepted in pop culture, scholars have taken a new step—looking more deeply at traditions that shaped Tolkien. Does that show that pop culture and scholarship are more connected than we may think—feeding each other, enabling each other?

Yes, I think that’s true—one of the things I was getting at in that paper (or trying to) is that the “reception” or “afterlife” of Tolkien’s works is increasingly complex. We can no longer think of it as a body of fiction being transformed via the genres and forms of pop culture (if that was ever the best way to think about it), and instead see it as a web of influences running into Tolkien’s corpus, and then different kinds of reception running out of it. I’ve been so interested by the way the more “pop culture” engagements with Middle Earth, like blogs and videos, are increasingly connecting with Tolkien’s own interests in faith, medievalism, etc.

You also discuss how, now that we’re past the “Tolkien is pop culture cool” phase, we’re seeing new interest in lesser-known works like his Arthurian poetry. Do you find it amusing or irritating that sometimes a writer’s “major” work has to become very popular before their “minor” works get similar attention?

A good question! I suppose it can be a bit irksome, and there’s always the scholar’s or fan’s wish to correct the distortions made by the market’s reception of a writer’s work. Agatha Christie is not a “cozy” writer of books about knitting and cups of tea, we want to cry. Dante is not some guy who wrote books about torture. Shakespeare did not pen endless sonnets about how much he liked girls. I suspect we all have our favorite “minor” works by authors—and it can be frustrating to see them treated less than fairly.

Your paper also talked about seeing Tolkien as a Catholic novelist, but in a different vein from other Catholic literary revival novelists like Evelyn Waugh or Graham Greene. Who are some Catholic novelists that he reminds you of?

Yes, I did say that—I must admit that the more I’ve reflected on that since, the more I think he is a bit like those two. The emphasis on the surprising and transforming power of grace, as well as its apparently “unfair” appearance in the world—that seems to be a theme they share at times. And the cultural framework of twentieth-century British Catholicism is definitely a shaping influence on them. I think it’s Michael Tomko who write illuminatingly about this—the distinctive atmosphere of British Catholics, who for centuries did not have equal civil rights or religious freedom in Britain, who were being grudgingly accepted in some quarters, but who had their own historical memories and touchstones, and lacked a place in the Whiggish narrative of Protestant national progress. I think you can read those novelists as sharing that. Of course, it’s also tempting to read Tolkien alongside another great British Catholic storyteller: G.K. Chesterton, with his little dumpy priest from Essex plodding along the pavements and roads, carrying terrifying secrets.

You’ve also written extensively about detective fiction. Did you become interested in that genre before or after becoming interested in the Inklings’ works?

At about the same time, though I’ve written about them at different times. I’ve always enjoyed Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers and Ngaio Marsh. I started sketching out some theories about how their novels worked, and what they had in common, nearly twenty years ago, but never got further than producing a few articles. Then my scholarly work on the reception of Shakespeare and the Bible took me back towards them, and they became a big part of my academic life. They’re enormously fun to write about, and everyone has an opinion on them!

I find readers who are interested in the Inklings, and in Golden Age Detective fiction authors like Sayers, don’t always intersect—not everyone realizes that Sayers was friends with Lewis and Charles Williams. When did you realize there was a connection there?

I’d agree—I read them separately for a while, and then there was a footnote in an edition of Sayers which quoted a letter to Lewis. That encouraged me to read them alongside each other—though I think it’s still useful to bear in mind their differences in interests and temperament!

There’s a theory put forward that the Golden Age of Detective Fiction was essentially religious—for example, Colin Duriez talks in his Sayers biography about her fitting into a 1940s Christian literature revival alongside people like Lewis and T.S. Eliot. Douglas G. Greene has talked about how even appears in apparently agnostic writers like John Dickson CArr. Any thoughts on how the detective story was essentially religious?

I’d certainly agree. W.H. Auden’s classic essay “The Guilty Vicarage,” published in the late 40s, argues that the detective novel is bound up with the search for a lost Eden, the sense of the Law and the ordering of the conscience. Dorothy L. Sayers left the genre to write religious plays and apologetics, and eventually translate Dante. Agatha Christie’s later novels emphasize Poirot’s Catholic identity. All the way through the genre the detective novel has quoted the Bible in various forms. The idea that the Golden Age novel was non-religious seems to me a hasty mistake by a late twentieth-century literary culture which assumed that the World Wars and modern physics had “killed off” a residual post-Victorian religiosity.

Your book Witchcraft and Paganism in Midcentury Women’s Detective Fiction noted that the Golden Age of Detective Fiction shows a strong interest in the supernatural. Obviously, your main point was how that applies to the way some of those writers depict witchcraft, but I’m curious: does that suggest there’s overlap between detective stories and fantasy or horror?

I think there absolutely is. That literally happens in the case of some writers. Agatha Christie’s work includes the detective novels and short stories, as well as some horror and supernatural stories—they’re collected in The Hound of Death, if memory serves. What strikes me on rereading those is not only how creepy they are, but how little different they are from her “rational” detective fiction. A Miss Marple story like “The Idol house of Astarte” swerves into explanation and logic at the end, but it could so easily have stayed on the path of folk horror. I argue in that book that some detective fiction does actually inhabit both the logical and the fantastical worlds at the same time Murder Is Easy by Agatha Christie, for example, and Look to the Lady by Margery Allingham. Those books allow the reader to explore them as both explainable mysteries and fantastical landscapes.

I was interested, and a little amused, to see that the recent television adaptation of Murder Is Easy involved feverish flashbacks of African traditional religion, and scenes in a private collection of witchy artefacts, none of which are in the original book—the writers obviously picked up on some of the same atmosphere to the novel.

Witchcraft and Paganism focuses on four of the “the Queens of Crime” from the Golden Age era (Agatha Christie, Ngiao Marsh, Gladys Mitchel, Margery Allingham), but you’ve also explored the fifth Queen, Dorothy L. Sayers. What are some things you find distinct about her work compared to these other four writers?

Yes, I didn’t look into Sayers’ work in that study because it seemed to be doing some rather different things. She’s a fascinating detective novelist to write about, because she seems to both exemplify some of the most absorbing elements of the genre, and also do them so well that she’s not typical of the form. That probably sounds rather over-enthusiastic! Certainly she’s distinctive in her depiction of the details of social life—reading a Sayers novel you get a strong sense of the surroundings people eat their meals in, what they’re wearing, how they speak, and why all those things matters. A novel like Unnatural Death gives us provincial tea-shops and luxurious Mayfair flats, it gives us the social trickiness introducing a new arrival to a parish church sale-of-work and the social trickiness of alluding to the flat a bachelor friend rents for the flamboyant opera singer to whom he is not married.

Sayers is much more concerned than Christie or Allingham to explore the social milieu of her characters. That means she can write books about a particular world—a London gentlemen’s club in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, the church in a small parish in The Nine Tailors, the office of an advertising agency in Murder Must Advertise, a clique of artists in The Five Red Herrings, an Oxford women’s college in Gaudy Night. In each of them the crime and its investigation is deeply connected to the kind of community this is, its internal life and its unspoken rules. In showing us an elaborately-plotted means of death she shows us a whole way of life. (As an aside, and perhaps as special pleading, I think this is also why some people find her novels off-putting and even troubling at times: people in the 1930s did not always have the moral or social values of modern people, and I think that’s more obvious in her novels than in those of Christie or Marsh.)

She’s also a compulsive reader and quoter—her novels are littered with epigraphs and allusions both inside the story about outside it. I argue at one point in Allusion in Detective Fiction that quotation in Sayers can be a way of characters looking for a connection with another person. Lord Peter’s Wimsey’s continual allusions, Miss Climpson’s carefully-annotated references to Shakespeare and Milton, the Dowager Duchess’ spiraling mentions of quotations which she never finishes or explains, are all depictions of their emotional worlds. When Harriet Vane enters the novels, quotation becomes a means of emotional fencing between her and Peter—it even becomes an erotically-charged game at times. That’s a rather distinctive element in her books.

Recently, you’ve written on social media comparing Sayers’ stories to Williams’ thrillers. What common territory do you see there?

They’re both writers working in popular genres, where lots is expected to “happen,” but they both give a sense of a much greater significance to the events taking place. I think both of them have that folk-horror flavor of something mysterious happening in a small English village, which is worked out in their different ways. They both have a strong sense of ritual. One of the most perceptive reviews I’ve ever read of Sayers’ work was William’s newspaper write-up of her book The Nine Tailors.[1] It’s a murder mystery set in a rural parish, but from reading his review you’d think it was an apocalyptic fantasy novel about strange powers unleashing the warring elemental spirits on an ancient land whilst mute angels watched from heaven. Which of course, in a way, it is.

Any thoughts on how Williams approaches witchcraft compared to the detective fiction writers you’ve discussed?

Compared to Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Gladys Mitchell and Margery Allingham? I think he’s a lot more attracted to the ritual magic elements of it. I’m not an expert on Williams, but I’d say he has a strong emotional investment in the kind of ritual tradition, expressed in things like Rosicucianism and haute magie, which was such a strong influence on (parts of) Wicca and modern pagan witchcraft.[2] His treatise Witchcraft carefully separates the high tradition from what he sees as its perversions. In Christie, Marsh, and Allingham, there is a suspicion of ritual magic and a definite skepticism about male magicians making claims to secret power. Characters like that often turn out to be deceiving themselves and others. Their interest in witchcraft is drawn more to the enchantment of the landscape, the small secrets of place and custom—things which were also influential on modern pagan witchcraft but in a different way. For Gladys Mitchell witchcraft can be a means of women recognizing something unspoken and alluring in each other.

What can you tell us about your latest book, Allusion in Detective Fiction?

It has been a long time in researching and writing, and has taken various forms over the last ten years! It brings together some of the intellectual obsessions I’ve been engaged with in my scholarly life, since the full title is Allusion in Detective Fiction: Shakespeare, the Bible and Dorothy L. Sayers. (There are, I should add, lots of other detective novelists discussed in it, from famous writers like Agatha Christie to lesser well-known Golden Age types like Henrietta Hamilton and Richard Hull.)

The book explores the role which allusion plays in the classic British detective novel. It argues that allusion is not an accidental feature of midcentury writing, nor is it a way in which detective writers tried to be more “literary” and pretentious than their genre allowed. Rather, allusion was a central part of the Golden Age novel, and became part of its artistic DNA in later decades.

I start by examining the situation of Shakespeare and the Bible in the mid-twentieth century. I detail the cultural and intellectual changes of the late Victorian era and the early twentieth century which caused people to read these texts differently—the scientific developments, the textual criticism and new translations, the changing role they played in public culture. I argue that there was a “textual crisis” in this period, when Shakespeare and the Bible, which had appeared to be fixed points underpinning a shared literary culture, began to look unsteady and shifting. In this situation, allusion was a means of trying to either probe how the world still made sense when seen through these books, or wrestling with the difficulties of them.

I show how Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers both allude to Shakespeare and the Bible in intricate and fascinating ways. Whose Body?, for example, involves a rewriting of The Merchant of Venice and the story of Jacob and Esau. The plot of A Caribbean Mystery involves Miss Marple combining quotations from Genesis and Revelation, and hinges on a hidden allusion to the Epistles. Murder Must Advertise plays an elaborate game with the constituent elements of Hamlet, whilst The Moving Finger makes Biblical jokes which would solve the mystery if the detective could recognize them.

In the second part of the study, I show how Sayers’ own novels then became a makeshift canon for the genre, which other novelists then alluded to and reworked. The same allusive habits which are so evident in her novels were exercised upon them in turn. I have great fun in examining how Christie and Marsh rework bits of Sayers—a particularly shameless moment involves Christie writing a novel which retraces parts of Strong Poison (a Sayers novel featuring Lord Peter) but involves a character called Peter Lord who is told by Poirot to leave the detection to the experts. I scrutinize a whole series of detective novels from the 1940s to the 2010s which allude to, react to, rewrite, or appropriate Sayers’ novel Gaudy Night. I conclude that all this textual activity established allusion as one of the marks of the classic British detective novel, and cemented Sayers’ role as a touchstone figure for the genre.

What are some future projects you can tell us about?

I’m currently writing the successor to Paths in the Snow, which is called Gold on the Horizon, and takes a literary journey through Prince Caspian and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. All being well, that should come out in time for Christmas 2024. I’ve been having quite a time tracing how Hamlet and King Solomon’s Mines are referenced in Caspian, for example, and how we can read the “Molesworth” books alongside Dawn Treader. I’m hoping to eventually complete a whole series of books taking this literary approach to Narnia; we’ll see how that goes.

There are always a few book projects simmering away in my notes and drafts. One is called The Barchester Tradition, and involves studying the way fiction writers in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have referenced and borrowed from Anthony Trollope’s “Barchester” novels. You’d be surprised by how many people engaged with those, from Ronald Knox to Agatha Christie to Joanna Trollope.

Another, which may take some time to develop, is a part-written detective novel of my own. It’s provisionally titled Murder at Michaelmas, and I come back to the manuscript every once in a while. Fiction is a new departure for me, but a rather exhilarating one.

More information about Jem Bloomfield can be found on his blog Quite Irregular or on Twitter/X as @jembloomfield.

INTERVIEWER FOOTNOTES

[1] Researchers who want to find this review (published in Williams’ “Murder and Mystery” book review newspaper column on January 17, 1934), can find it in The Detective Fiction Reviews of Charles Williams, 1930-1935, edited by Jared Lobdell (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2003), pp. 105-106.

[2] For more on Williams’ firsthand experience with Rosicrucianism and an offshoot of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, see the Fellowship & Fairydust interview with Dr. Sørina Higgins.